It’s 2020, which means another Leap Year is upon us once again! For an event that only shows up once every four(ish) years, traditions associated with it are fairly scattered and inconsistent. But if any one tradition is firmly tied to Leap Year, it’s that of women proposing.

Here’s some history on how that might have come to be.

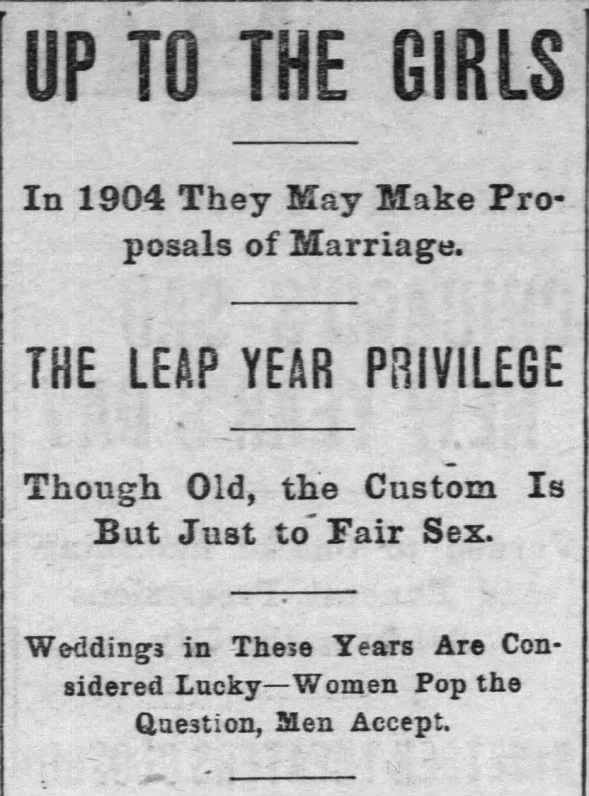

Up To The Girls Sat, Jan 2, 1904 – 2 · The Topeka Daily Herald (Topeka, Kansas) · Newspapers.com

Up To The Girls Sat, Jan 2, 1904 – 2 · The Topeka Daily Herald (Topeka, Kansas) · Newspapers.com

St. Bridget’s Request

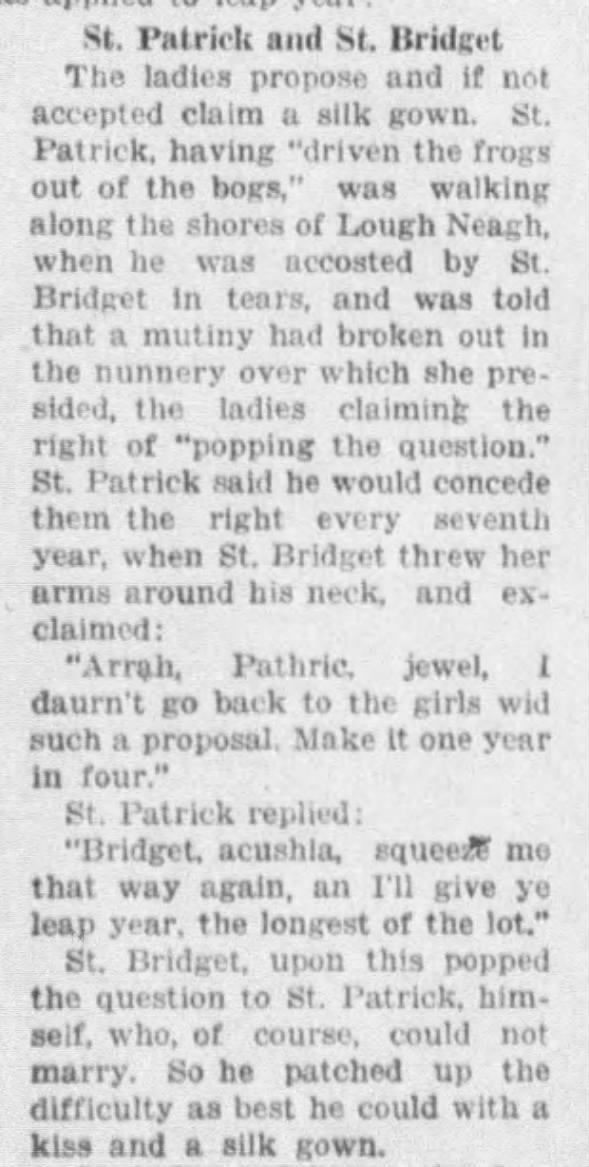

Legend says that St. Bridget, back in the 5th century, had some thoughts on proposals that led to the tradition as we know it today. The clipping below shares one version of what happened.

One version of the St. Patrick and St. Bridget origin of Leap Year proposals Mon, Feb 27, 1928 – 4 · Tampa Bay Times (St. Petersburg, Florida) · Newspapers.com

One version of the St. Patrick and St. Bridget origin of Leap Year proposals Mon, Feb 27, 1928 – 4 · Tampa Bay Times (St. Petersburg, Florida) · Newspapers.com

What’s a single young man to do if he must say no to a proposal? Give the young lady an apology gift, of course. The payment of a silk dress is a common recurring part of the proposal tradition.

Queen Margaret

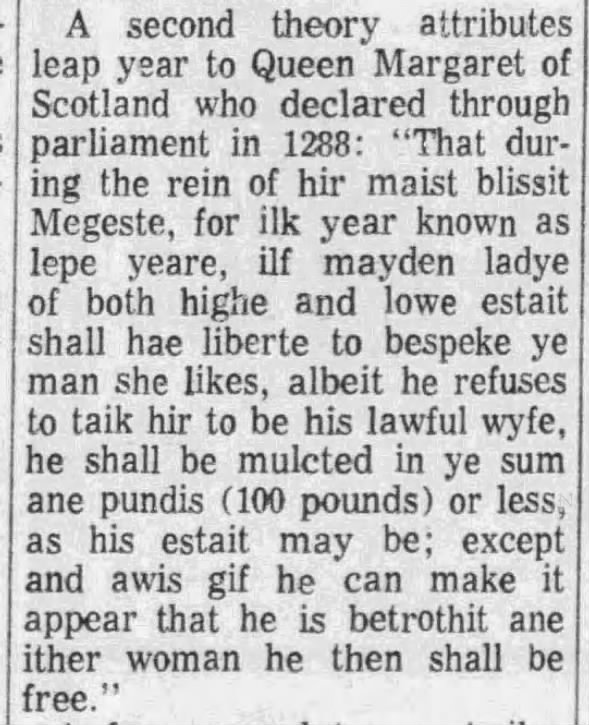

The idea of a payment for spurned proposals is reinforced in this next part of Leap Year lore. As the story goes, in the year 1288, Queen Margaret of Scotland made it law that a man who dared turn down a perfectly good proposal without proof that he was already otherwise spoken for must pay—quite literally.

Queen Margaret’s 1288 law, according to legend Sat, Dec 30, 1967 – 15 · Edmonton Journal (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada) · Newspapers.com

Queen Margaret’s 1288 law, according to legend Sat, Dec 30, 1967 – 15 · Edmonton Journal (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada) · Newspapers.com

Yet, despite the very specific year of 1288 and decades of dedicated historian research, no such law has ever been proven to exist. Not only that, but the actual Queen Margaret on whom this legend is based was born in 1283, making her 5 years old at the time of the law. So this bit of Leap Year history is almost certainly nothing more than a fun bit of mythical trivia.

The Scarlet Petticoat

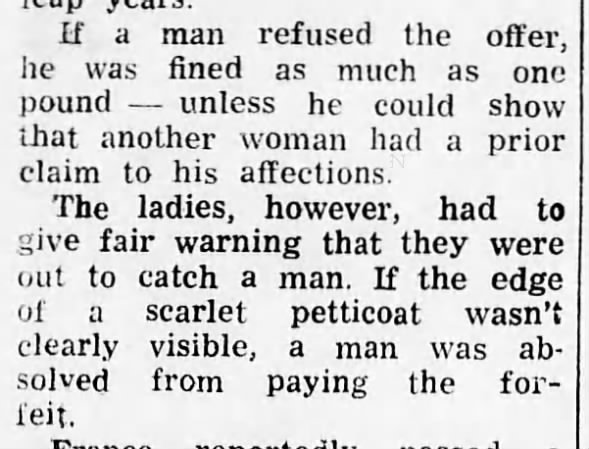

Perhaps as a reaction to all of these rules for the proposee, a more recent bit of lore adds a restriction for the ladies. Sure, a man must still pay for refusing, but the whole transaction could be nullified for the lack of a bright red petticoat.

Absence of a red petticoat cleared a man of paying a leap day proposal fine Thu, Jan 14, 1960 – 1 · The Brockway Record (Brockway, Pennsylvania) · Newspapers.com

Absence of a red petticoat cleared a man of paying a leap day proposal fine Thu, Jan 14, 1960 – 1 · The Brockway Record (Brockway, Pennsylvania) · Newspapers.com

Leap Year Critics

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this tradition based on open season-style female proposals has often been derided in articles, cartoons, post cards and more over the decades. Men were considered, generally, to not be fans of the whole idea. Cartoonist Al Capp even played off the whole idea in his comic Li’l Abner, leading to the creation of Sadie Hawkins Day.

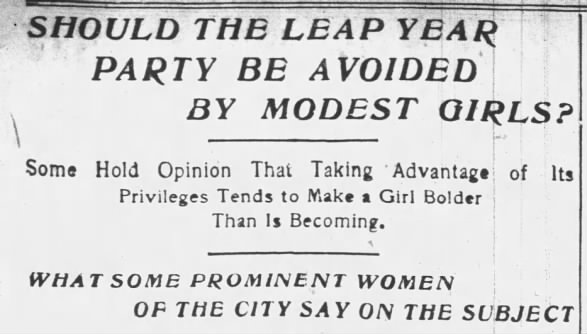

Many women looked down on it as well, thinking it made girls unbecomingly bold to the point of being embarrassing for all involved.

Some find Leap Years “Make a Girl Bolder Than Is Becoming” Mon, Mar 21, 1904 – 5 · Buffalo Courier (Buffalo, New York) · Newspapers.com

Some find Leap Years “Make a Girl Bolder Than Is Becoming” Mon, Mar 21, 1904 – 5 · Buffalo Courier (Buffalo, New York) · Newspapers.com

Now, as gender roles shift and progress, the idea of the “Leap Year Girl” doing things she could never otherwise do is fading into the past. Who knows but that the tradition will continue to change with it?

Find more clippings about Leap Year and the “Ladies’ Privilege” with a search on Newspapers.com. And follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for more historical content!

Like this post? Try one of these:

The “Jolly Batchelor Girls” in Kansas sure don’t look very jolly.