Historical newspapers contain thousands of advertisements and testimonials touting miracle cures for sickness, aches, and pains. With the benefit of hindsight, we now know that

Author: Jenny Ashcraft

Barbie burst on the scene in March 1959 at the American Toy Fair in New York City. The 11.5-inch-tall Barbie dolls were the brainchild of

William Jackson Smart, a Civil War veteran, experienced the pain of losing two wives and the profound responsibility of raising his children as a single

It’s been 75 years since the HMT Empire Windrush, a former troop carrier turned migrant ship, arrived at Tilbury Docks near London on June 21,

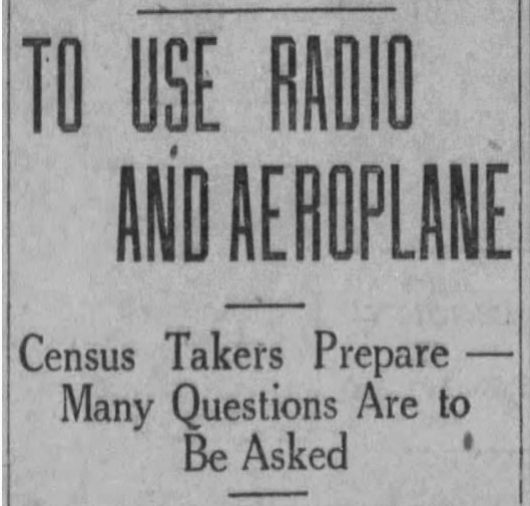

On June 1, 2023, the Canadian government will release the digitized records of the 1931 Census of Canada. This highly anticipated event will reveal a

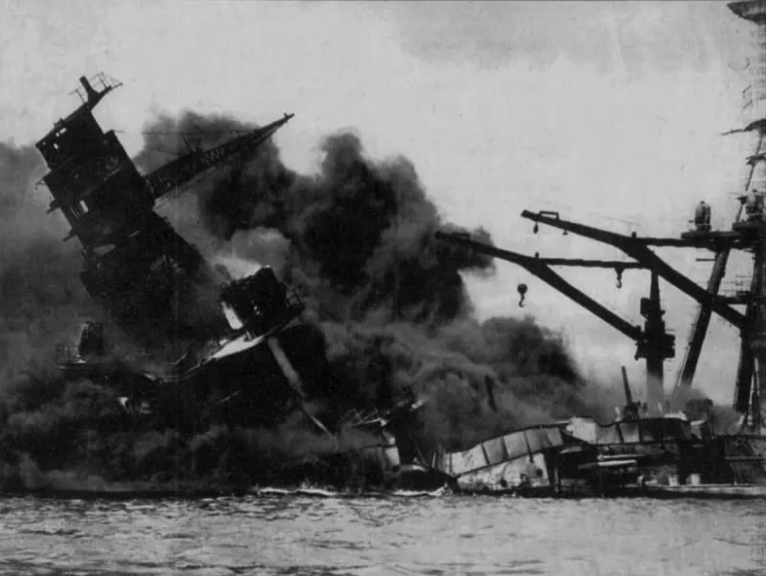

Even though it’s been 82 years since the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, those who lost family members on December 7, 1941, continue to mourn

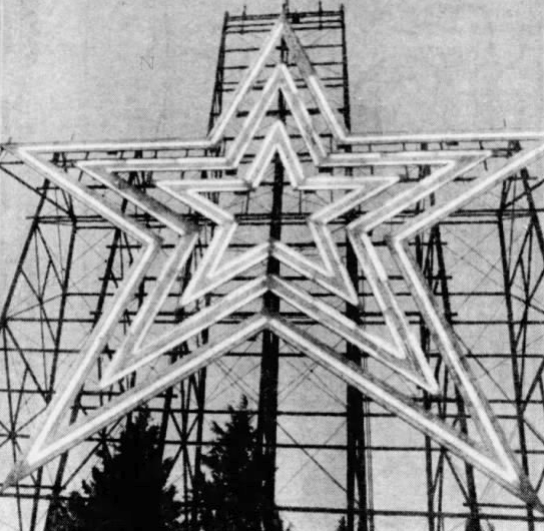

We’re pleased to announce the addition of The Roanoke Times to our collection of Virginia papers. Founded as the first daily paper in the area

In 2018, Elizabeth Bell, a member of our Newspapers.com™ team, made a surprising discovery about her family history. She received the results of her Ancestry®

If you have ancestors from Indian Territory or Oklahoma or are interested in Oklahoma history, you are in for a treat. We’ve partnered with the

Newspapers are an incredible resource for learning details about your ancestors’ lives. Simple searches can yield surprising insights. Expanded searches might result in genealogical breakthroughs.