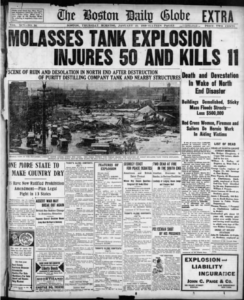

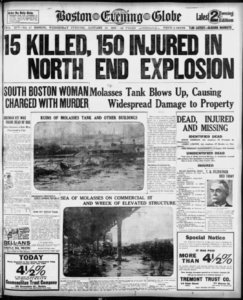

Does the scent of molasses linger in your home long after the holidays? The Great Molasses Flood of 1919 left residents from one city claiming they could smell molasses for decades. On January 15, 1919, a giant tank holding 2.3 million gallons of molasses burst open in Boston’s North End neighborhood. It flooded the streets creating a 15-foot wave of molasses that carved a path of destruction. The sticky quagmire killed 21 people and injured 150, paving the way for more stringent safety standards across the country.

During WWI, molasses was distilled into industrial alcohol and used to produce military explosives. The Purity Distilling Company set up shop in the densely populated North End neighborhood in Boston. The area was home to many immigrants, and the company encountered little opposition when they constructed a 50-foot tall, 90-foot diameter molasses tank, just three feet from the street in 1915.

Days before the deadly explosion, a ship delivered a fresh load of warm molasses. It was mixed with cold molasses already in the tank, causing gasses to form. With the tank filled to near-capacity, a later structural engineering analysis revealed that the walls were too thin to support the weight, and there was too much stress on the rivet holes.

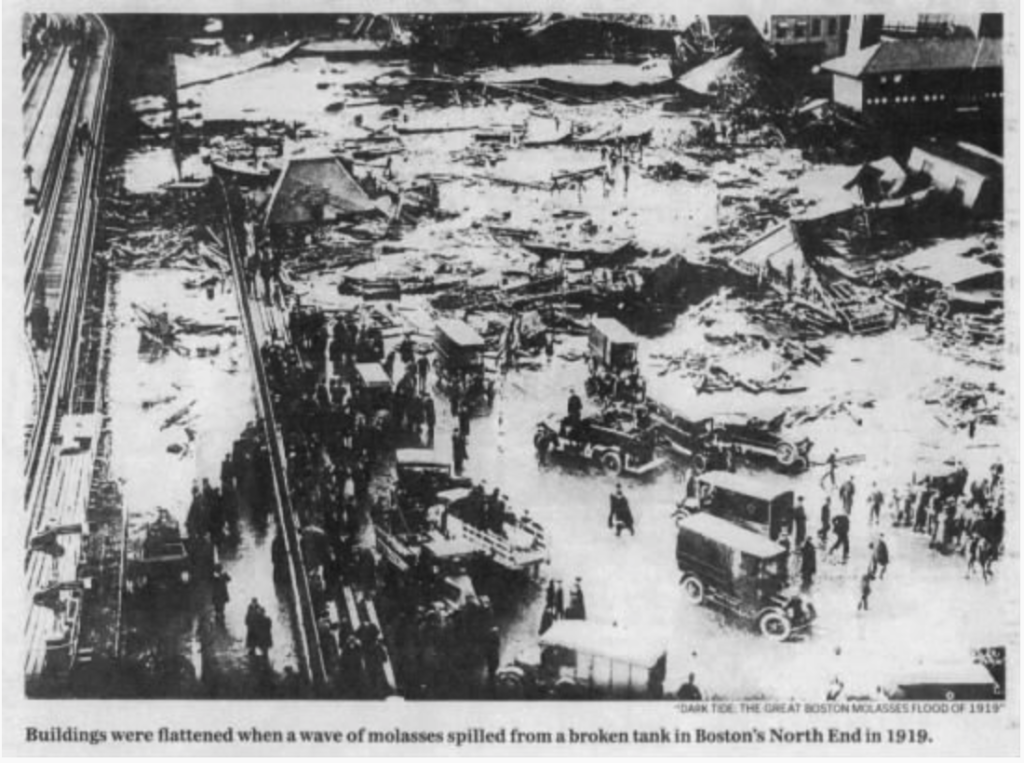

Around 12:30 p.m. on January 15, 1919, workers stopped for lunch and a group of firefighters in a nearby firehouse sat down for a game of cards. Suddenly firefighters heard a strange staccato sound. It was the rivets on the molasses tank popping off. Other witnesses described a low rumbling sound. Before anyone could react, the tank of molasses burst, sending a rush of air that hurled people off their feet. A tsunami of sticky syrup poured over bystanders and horses, and knocked buildings off their foundations. The resulting river of molasses ran through streets and passageways, filling cellars and basements. A one-ton piece of steel from the vat flew into a trestle of elevated railroad tracks, causing the tracks to buckle.

First responders rushed to help but were slowed down by knee-deep sticky molasses that had become thicker in the cold air. They labored to find survivors and recover the dead. Initially, there were concerns that the bursting tank was caused by sabotage or an outside explosion (a claim that Purity Distilling Company clung to). Officials later determined that faulty tank construction was the cause. Workers spent months cleaning the molasses mess by sprinkling sand and hosing down the streets with saltwater.

The tragedy led to many lawsuits and more than 100 damage awards. It also spurred changes in building codes with more stringent building regulations, first in Boston, then in Massachusetts, and then across the country.

If you would like to learn more about the Great Molasses Food, search Newspapers.com today!

Like this post? Try one of these:

What a sweet story and quite true. They say on warm summer days you can still smell a scent of molasses in the air around the fire station!

I have also heard that on a warm muggy day the smell of molasses is noticeable.

That may be mole’s asses.

A friend who lived in the North End for a while swore it was still noticeable when it got really hot and humid, even as late as the 1990s.

It’s great you are putting stories out so the younger people can read about what happened before our time.

That’s fun and all but this site hasn’t updated their papers in a VERY long time. I’ve watched the circle list go thru and it’s always the same papers over and over.

Love this article. This would also serve as a good topic for a science class . The students would love to hear this sticky story and understand just why it occurred.

Agree…Kids who don’t know history are deprived of a well rounded education.

I enjoyed reading this bit of history of Boston. Keep sharing bits of historical information to us. Thanks.

Their Boston Globe archives is one of the last best things they ever did a long time ago.

I was delighted to read this story of yore. I had never heard of a molasses flood.

Stories of the past are not only good for youth but also for 90 year olds.

Read “The Dark Tide”. Great read!

I never heard about this until today. It’s wonderful that my generation & future generations are able to read about our past histories.

It’s true about the smell of molasses. It is very faint but every once in a while in the hot summer a construction crew will dig up part of the street with cobblestones under layers of asphalt. Sure enough there will be traces in the cracks sometimes and you will smell the traces of syrup.

I believe the smell of today is a fantasy of the mind. Too much rain and snow has washed away the possibility of an Oder. A simple way to keep a story in history going!

Why don’t you tell of prior so called pandemics the U.S. has had in the past 150 to 175 years. I’m sure they would like to here of how millions died of yellow fever and other diseases that nearly destroyed the U.S. in earlier history. For covid is no more dangerous today than the fevers and other diseases of yester years gone by. The only difference is that the U.S. wasn’t as populated back then, but it was just as dangerous . At least back then people had common sense and didn’t go ape shit crazy about it. They took care of the problem and moved on rather than spreading fear into the people with a scaredemic. This has been nothing more than a way for the rich to get richer and the poor to become poorer.

Imagine if we had shut down our bars and restaurants everytime we had a polio outbreak?

I remember the swimming pools and theaters being closed when there was a case of polio in town.

Here come the denialist partisans with their historically inaccurate takes ruining every comments’ section.

The Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic of 1793, for example, led to a mass quarantine. Social distancing went into full effect, with people covering their noses, hands and necks, never shaking each other’s hands and avoiding contact. If someone ever went outside, they would walk in the middle of the street to prevent themselves from passing by houses wherein people had died. Many fled from Philadelphia in panic, while neighbouring cities imposed heavy quarantines on refugees and goods. In New York, patrols were set up to monitor entry to the city, and the general sentiment was of fear and hysteria. A very similar thing happened worldwide during the 1918 spanish flu pandemic, with some group from San Francisco even forming an “Anti-Mask League” to protest against preventive measures.

People back then were as much as hysteric as we are now, if not more. Of course, denialism and conspiracy theories are also much older than we generally think of.

How spot on! Thanks for doing research. The facts are not a surprise. People are always the same not matter what or when. Most times if you really want to change something, you have to change people’s way of thinking and doing.

Thanks for the accurate, scholarly historical correction

You are 100% correct! Well said‼️

Why was this blog shut down for so long with comments all disabled?

The authorities are practicing how to implement a “blackout” in the US of A

The real grid X perhaps?

This wasn’t an amusing occurrence. 21 people died and 150 were injured.

Great to read about the past. Comments are good especially about teaching in school

My name is Sylvia. I made a comment about school use . It can open young minds up to learn lessons from what happened, in subjects like math, science, chemistry, engineering and if it only leads to making them want to read more that’s an accomplishment in itself.

Hi. My name is Cortana I can be used in school use and open young minds up.

What a interesting article. I never heard of this incident. Love these kinds of stories.

I went to High School at 12 Tileson St. was Catholic School in the 1960’s. How close to it was I.

This was the 1st time I heard this story. Amazing. Thanks for sending it.

When I went to the U.S. Navy Nuclear Power School back in the mid 50s this story was used to explain why the reactor must be heated up slowly because of fhe type of steel it is constructed of and will crack if stressed. Note that the incident occured in the winter abd was under great stress. It is interesting to me that the story is still around. Bob Jones (U. S. Navy retired)

Did anybody clock the speed of the onrushing tide of syrup? My 6th grade teacher always said I was slower than molasses in January, and I’d like to know just how fast it was.

Good question Wayne. While respecting the tragic events and seriously empathizing with those families so terribly impacted by the death of loved ones your question remains as reasonable and very interesting. That awful thing was like a tragically serious, slowly surging, sickening sweet, sticky tsunami, a surreal Blob, a heavy mass of molasses whose possibly cold air hardened weight coupled with the cold hardened cobblestones beneath, may have sped it up some. But I’m thinking that, unless iced over, the best laid cobblestone streets are/were still a bit rough, creating a natural speed brake for that unbelievably monstrous, indiscriminately murderous molasses mauler. I hope so anyway, which hopefully would have given those poor victims a better chance of outrunning the deadly thing which must have been approaching from strangely multiple directions. Just imagine what those who safely escaped must have eventually thought once natural grieving had begun to settle in; and, after enough time had passed allowing those survivors to just reflect on what in the hell was this evil thing that just happened up in here, and why? I could see their desperation of thoughts leading them to worry about if now this then what in hell could be next. Wow, it must have been so unsettling to those poor souls struggling just to get by in life. I have a seriously saddened empathy with all those families.

But still , Wayne , I think your quest to learn the relative speed of the deadly incoming wall of syrup is valid, if asked in order to give you more perspective into the nature of your teacher’s opinion of your slow walk to the chalkboard or perhaps a thoughtfully slow and deliberate answering of a teacher’s questions which may have seemed somewhat odd to you. It’s all in the perspective. And maybe some physics professor might be intrigued enough to model something similar to estimate the speed of that deadly wall of molasses in that tragic winter in Boston., Literally stuck in a tsunami of tragedy

For all those people affected my heart bleeds for real. It must have been so God awful then; and, to now hear of it again for those whose ancestors suffered, must bring back terrible memories of family stories of sadness. So, my thoughts and feelings go out to them all. I’m so sorry something like that happened to such good people trying to get through another cold winter. May God Bless those who suffer. And, IThank you.for sharing a feeling that needs no forgetting.

Sounds like they were in a very sticky situation!

Nice one lol too funny..

Interesting. I’m reading about this in the book Dark Tide now.

I’d never heard of it before.

Not to be overly critical, but the story as written seems self-contradictory as to the cause of the failure. Never mind the company’s self-serving claims of sabotage or an outside explosion. According to the article, either the walls were too thin (a design flaw) or the construction was faulty (a manufacturing defect). Maybe both? I seem to remember seeing a metallurgical failure analysis of this event published years ago. Maybe I (or some other reader) can find it and report back.

Following my first comment, a quick Google search revealed that very soon after the event, an MIT professor declared that the walls of the tank were too thin and that too few rivets were used. This was the main claim of the plaintiffs in the civil suit. An auditor, after exhaustive testimony and study, declared that there were multiple causes, including inferior material and construction, a low factor of safety (in other words, insufficient wall thickness for the load) and something he called secondary stresses. I think the latter was a reference to the theory that the recently added warm molasses had raised the internal pressure by generating carbon dioxide. An analysis by a metallurgist and structural engineer a few years ago (Ronald Mayville) agreed that the walls were too thin (by a lot), but also blamed the design of a “manhole” on the tank, which was the likely point of origin of the failure, and that, by design, was insufficiently reinforced. Finally, he blamed the quality of the steel. All metallurgists know that structural steel in 1919 was not nearly as clean as it is today. Mayville blamed low Manganese content in the steel plates that were used to construct the tank – a virtually unavoidable composition at the time. Low Mn may be associated with other differences in composition that reduce the toughness of the steel. So it seems that even now there may be honest disagreement as to the primary cause(s) of the tank’s failure, but I think the auditor, way back then, pretty much had it right: there were multiple causes, both in design and manufacture. I think it’s odd that some folks at the time said that the disaster could have been prevented by testing the finished tank. Who is to say that the test wouldn’t have unleashed a potentially lethal tidal wave of water?

Sadly, my great uncle, William A. Duffy, was killed in the flood while working outside in the Boston paving yard next door to the tank.

Very interesting story. I had never heard of this unfortunate incident. I can’t even imagine what the survivors had to endure in the aftermath of this destruction and loss of loved ones.