Today’s high-performance cars can have upwards of 700 horsepower. But in the 1800s, typical horse and buggy transportation consisted of one or two horsepower – literally! Horses and other animals including oxen and donkeys provided the primary means of transportation all over the world through the nineteenth century. A single horse could pull a wheeled vehicle and contents weighing as much as a ton.

Transporting people and goods was a costly venture in the 19th century. Animals required large quantities of food and water. Roads usually consisted of two dirt paths with a grassy strip in the middle and they were rough and bumpy. Wagon wheels formed deep ruts that in some places are still visible today, and those same dirt paths turned into a muddy mess when wet.

To meet transportation needs, a variety of types of wagons were available. Some were simple farm wagons, others elegant private carriages. Stagecoaches provided public transportation. Let’s take a look at some of the options our ancestors used for travel in the 1800s.

Buckboard Wagon: The no-frills buckboard wagon was commonly used by farmers and ranchers in the 1800s. It was made with simple construction. The front board served as both a footrest and offered protection from the horse’s hooves should they buck.

Gig Carriage: A gig was a small, lightweight, two-wheeled, cart that seated one or two people. It was usually pulled by a single horse and was known for speed and convenience. It was a common vehicle on the road.

Concord Coach: American made Concord coaches were tall and wide and incorporated leather straps for suspension that made the ride smoother than steel spring suspension. They were also extravagant, costing $1000 or more at a time when workers were paid about a dollar a day. Wells, Fargo & Co. was one of the largest buyers of the Concord coach. Today the company still displays its original Concord Coaches in parades and for publicity.

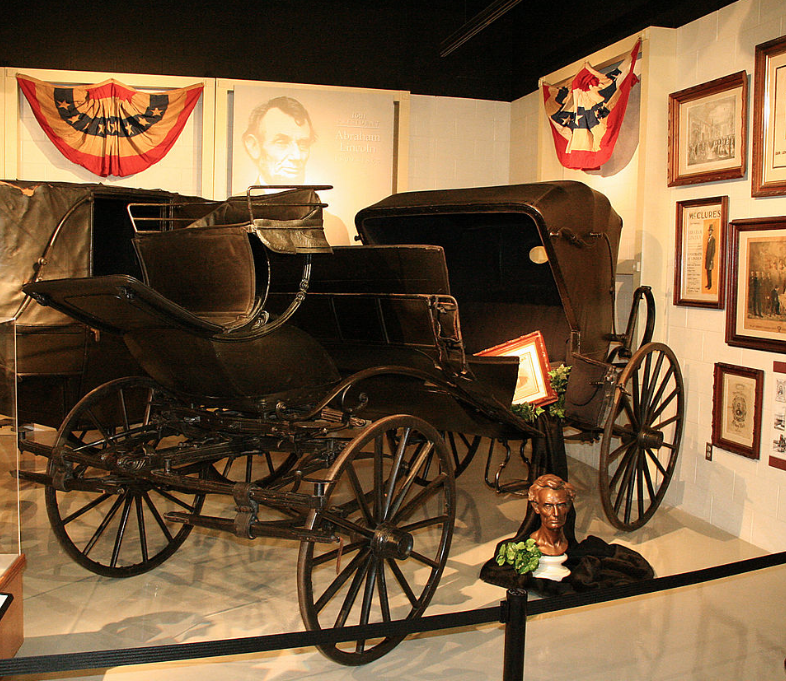

Barouche: A barouche was a fancy, four-wheeled open carriage with two seats facing each other and a front seat for the driver. There was a collapsible hood over the back. It was a popular choice in the first half of the 19th century and was used by the wealthy. It was often pulled by four horses. This barouche carriage carried Abraham Lincoln to the theater on the night of his assassination.

Victoria Carriage: The Victoria carriage was named for Queen Victoria and renowned for its elegance. It was a low, open carriage with four wheels that seated two people. It had an elevated seat for the coachman.

Phaeton: The Phaeton was a sporty four-wheel carriage with front wheels that were smaller than the rear wheels. The sides were open and that exposed a gentleman’s trousers or a lady’s skirt to flying mud. The seat was quite high and required a ladder to access. Phaetons were fast, but also high-centered leaving them vulnerable to tipping. They were pulled by two or four horses.

Landau Carriage: The Landau carriage was considered a luxury city carriage that seated four. It had two folding hoods and was uniquely designed to allow its occupants to be seen. It was popular in the first half of the nineteenth century. Pictured here is Queen Elizabeth in a Landau carriage.

Brougham Carriage: Designed by England’s Lord Brougham, the Brougham carriage was lightweight, four-wheeled carriage with an enclosed carriage. It was popular because passengers sat in a forward-facing seat making it easy to see out. It was also lower to the ground and easier for passengers to climb in and out of the carriage. The Brougham was driven by a coachman sitting on an elevated seat or perch outside of the passenger compartment.

Rockaway Carriage: The Rockaway originated on Long Island. It was a popular vehicle with the middle class and the wealthy. One distinguishing feature of the Rockaway was a roof that extended over the driver, while the passengers were in an enclosed cabin.

Conestoga Wagon: The Conestoga wagon was large and heavy and built to haul loads up to six tons. The floor of the wagon was curved upward to prevent the contents from shifting during travel. The Conestoga was used to haul freight before rail service was available and as a means to transport goods. Conestoga wagons were pulled by eight horses or a dozen oxen and were not meant to travel long distances. The Conestoga wagon is credited for the reason we drive on the right side of the road. While operating the wagon, the driver sat on the left-hand side of the wagon. This freed his right hand to operate the brake lever mounted on the left side. Sitting on the left also allowed the driver to see the opposite side of the road better.

Prairie Schooner: As families moved west, a prairie schooner pulled by teams of mules or oxen was a common choice. It was like the Conestoga wagons, but much lighter with a flat body and lower sides. They were typically covered with white cloth and from a distance resembled a ship. Travelers in prairie schooners often traveled in convoys and covered up to 20 miles a day which meant an overland trip could take 5 months.

Stagecoach: The stagecoach was a public vehicle where passengers paid to ride long distances. Stagecoaches ran on a schedule and were typically pulled by four horses. Periodically, horses were changed out for a fresh team.

To learn more about these types of carriages and others, search Newspapers.com today.

Very informative! Thanks!

Transportation a favorite subject of mine. Great, concise information and wonderful pictures to accompany the article. I enjoyed it very much. Thanks

I wish I could have been Born During the Stagcoch days.prombely because I have always loved the wild Wild West.. Being raised on the Good ol Western TV shows Gunsmoke ECT…as a young boy I always was a Cowboy at heart.. again I would have loved to be back in those days and times..life was very hard. But to have met some of the Great Cowboys in those times would have made be very happy…thank you Bill Ragle. Anderson IND…

You might change your mind if you had actually traveled in one. They had springs, but no real shock absorbers so riding in one was a rough ride in areas where there were no improved roads. In the Old West you could be stuck on one for ten or twelve hours a day for days on end. See Mark Twain, Roughing It.

Having read about the road across Pennsylvania, I can imagine the Waggoners driving Conestoga wagons and smoking their “Stogies”, stopping at inns where waggoners took their seat inside to sleep on before the fireplace and put their animals out to pasture. The inns were often located at the bottom of a hill and thus would rent out extra livestock so the wagon could make the hill. Drovers were taking livestock on foot east to the markets and waggoners hauled manufactured goods to the west. Stagecoaches from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh stopped only to feed and water or exchange the animals so that is when the passengers could get a bite to eat and other necessities! With all the animals on the road it must have been quite an aromatic journey.

History can bore, but to me the

horse ‘n buggy articles with pictures/drawing are interesting fun. Movies seemingly

have been de-facto educational

means, and I perceive the movie

makers are at least informal

teachers/professors. I haven’t visited

museums for years. If I subscribed

to your newspaper service, I would

be expending too much time there!

Some libraries use microfiche for

their newspaper collections, and

archaeologists should be happy

for the foresight. Btw, there is a

recent report in the New York Times

of a serious if not catastrophic fire

that destroyed pop music masters.

A commenter says he cried upon

reading the revelation of the d fire

of about ten years ago in Hollywood.

Thanks for preserving our cultural

history by internet website maximally

accessible.

To Kyle: this page was about horse and buggy. Did you not get that? It was not about conspiracies nor CIA nor bots. Did you even bother to read the bits about the horses and buggies? Or do you just like to see your own words in print on the screen.

Very interesting and helpful article on the many varieties of carriage. I find it interesting that as many different types of coach-bodies there were, that the carriage wheels varied so little. You’d think someone would have come up with a wider wheel track to prevent getting bogged down in those rutted roads!

Remember those narrow wagon wheels were towed, not driven, wheels as in a motor vehicle. A wide rim on a towed wheel would just bog down hopelessly or at least increase towing resistance enormously in soft mud or sand. A wide rim on a wheel increases traction if it is driven but also greatly increases rolling resistance if towed. That’s one reason why heavy trailers have multiple narrow wheels rather than single very wide ones.

Very interesting, thanks for that info!

My Italian immigrant great grandfather ran a fruit stand beside the Hotel Charlotte, in Charlotte, NC. A late 1880s newspaper reported that a hay wagon’s “tree” broke as it was cresting a hill and turning right onto Tryon St in Charlotte. The horses reared and galloped down Tryon before hitting a tree and knocking over my ggrandfathers oranges. Dirt streets, horses, wagons, hay etc. –it all seems so improbable looking at Charlotte today. Do you know what a “tree” on a wagon was?

I believe “Tree” would likely be another name for the “tongue” which was a wooden spar analogous to the tongue on a modern trailer. In the case of a heavy, 2 axle wagon, it would be attached to the front axle assembly, which would be on a swivel so the axle, and the tongue attached to it to make a “T”, could pivot to either side to turn the wagon. The draft animal’s harness would be attached to either side of the wooden tongue or tree. If this tongue spar broke, only the reins would be connecting the draft animals to the wagon.

Ms. Ashcroft your article was well done. I enjoyed it very much, especially the explanation of how we ended up driving on the right side of the road. Also, enjoyed some of the informative comments from other readers. Thank you.

Thanks so MUCH for this. My ancestors lived in Brookline Vermont, and mid-century a whole community of them went west, stopping in Nicolette Minnesota. Some went on to Monterey California, some stayed in Nicolette, but a whole huge group went right back too Vermont a few years later. I’ve been trying to imagine the transportation options. I had decided one Conestoga wagon, but your article makes me think thatThe Prairie Schooner is the most likely vehicle. What do you think?

I’d live a similar article in options for transportation in the 17th century! How did early settlers (and all their people and fear) get from coastal ports to inland destinations?

If you look at the early migration in North America, you will see that much of it followed the rivers. People could walk by the rivers and be sure they were near water necessary for life. Or they could build boats/rafts and float down stream with their possessions. In effect, the rivers were liquid highways.

Thank you for this interesting article on the horse and buggy. I enjoyed reading it. I have been doing some family history research and have discovered that my 2x great grandfather was a carter in Glasgow in the mid-19th century; and that his son, my great grandfather, was a post boy or postillion who transported mail by horse-drawn cart first in Lochaber, Scotland, and then in the Outer Hebrides. Finally, my own grandfather was a horse transport driver with the ammunition column of the !st Canadian Infantry Division in France in World War I. He was seriously injured, but not killed, when a shell exploded adjacent to his team and he was thrown from his horse.

My grand father Gilbert Stanley Waters built buggies and carriage in New Bern, NC between 1892 to 1917. His brother in-law, Charles Thomas Randolph, Sr. preceded him in the buggy business in Washington, NC and subsequently in New Bern, NC., where he built the Phaeton Buggy.

I have written about my grandmother going to Las Vegas, NEW MEXICO in early 1900s before New Mexico became a state. I am still wondering her modes of transportation from Southern Ohio to New Mexico. Great Article, Thank you!

My guess from reading some writings from around this time is that taking a horse drawn carriage wasn’t that much faster than walking. Maybe five or six miles an hour?

For sustained walking, figure on about 2 miles an hour with a 5 or 10 minute breather every hour, especially if you are carrying a pack over rough terrain, even less. Military forced marches can reach 40 or even 50 miles in a day, but that is an emergency measure with a high risk of running into an enemy with your men dog tired.

I walk a lot in Manhattan. I can usually do close to 60 blocks (3 miles) an hour if not encumbered with anything heavy to carry. (I

am not an athlete or fitness fanatic.) I don’t take many rests or breaks and can keep it up for 5 hours or so with only a couple of brief stops of a few minutes. I say this merely to make the point that walking, say, 5 or 6 miles in a couple of hours is very doable. I seem to recall reading about soldiers walking 20 miles per day on average when traveling to a new site. They would presumably have been encumbered with heavy backpacks.

For those interested in the comparative walking speeds and endurance levels between humans and horses, read about “Ride & Tie.” I am not a participant so I don’t have first hand knowledge, but I’ve heard it described at some length by friends. This competitive sport involves moving 2 people & 1 horse over a long distance of often semi-difficult terrain. It is based on a practice supposedly developed by Native Americans for covering ground at an optimum rate when 2 people have to share a horse. The basic idea is that one person starts out running/jogging at the fastest sustainable pace for ½–1 mile (distance varies according to participants training and preference) and the other rides off on the horse at a brisk pace. After the agreed upon distance, the rider ties off the horse to rest and runs/jogs off at his best pace for the planned distance. The first runner runs up to the horse, gets on and does the same routine, over and over. Ridden like this, a horse and two people in reasonable shape can cover 40 miles in 7-8 hrs (5-6mph) which is probably about twice as fast as a human can do it over a similar distance. Supposedly, the long experience of Native Americans hit upon this method for covering very long distances of ground at the fastest possible speed without injuring or killing the horse (or the runners!). It is said to be pitched to the natural strength of the horse which is sprinting or middle distance running, which he can do all day IF he gets the periodic rests of the tie-off period.

I also enjoyed reading about the wagons etc, My Grandfather John Hillyer, 1886-1970,

told about his father and neighbors making the 17 mile trip from Bloomingdale, Fl to Tampa, Fl in the 1890’s by a team of two oxen, the oxen pulling a loaded wagon would make about 2 miles and hour, there fore 8.5 hours per day, there was no traveling at night, they would stop for the night east of Tampa, at a stream called 6 mile creek,(now a flood control canal ), go into town the next day to sell their wares and buy supplies then return to the creek, on the third day return Home, By contrast., the H.B. Plant Railroad would pull into the Tampa Bay Hotel, owned by H.B. Plant, Tampa Fl. the same hotel used by the Lt. Col. “Teddy” Roosevelt and other Officers of the U.S. Army, staging to board ships to deploy to Cuba, for the Spanish American War. Yes interesting times.

In 1834 Charles Shipman and his daughters, Joanna and Betsey, traveled by a horse drawn vehicle from Athens, Ohio to Baltimore, where the vehicle and horse(s) were left at a stable while they traveled by steam boat up the Chesapeake, then took a steam train across a narrow neck of land to the Delaware River where they continued the trip by steam boat to Philadelphia. Returned to Baltimore, then travelled to Washington, visited President Jackson, and returned home by a different route as recommended by the President.

The trip was recorded in a journal kept by Joanna Shipman and later published in a small book. No description of their vehicle beyond “got into our carriage”. Their route followed very closely to what is US 40 today on the way to Baltimore. They left on Monday October 6 and, on Friday, November 14, she wrote: “On the road to Athens and arrived at the close of the day. Found mother and Charles all well and glad to see us, as we to see them and home again.”