If you’ve been tuning in to the new Netflix series Tidying up with Marie Kondo or read Kondo’s bestseller The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, you’re familiar with her war on clutter. As part of her KonMari Method, she famously encourages people to keep only possessions that “spark joy.”

But Kondo’s decluttering philosophy wouldn’t have been popular in the U.S. in the mid- to late 19th century. In fact, the opposite philosophy seemed to reign—the more objects on display in your home the better, particularly if you were wealthy or aspiring to be so.

The Rise of Bric-A-Brac

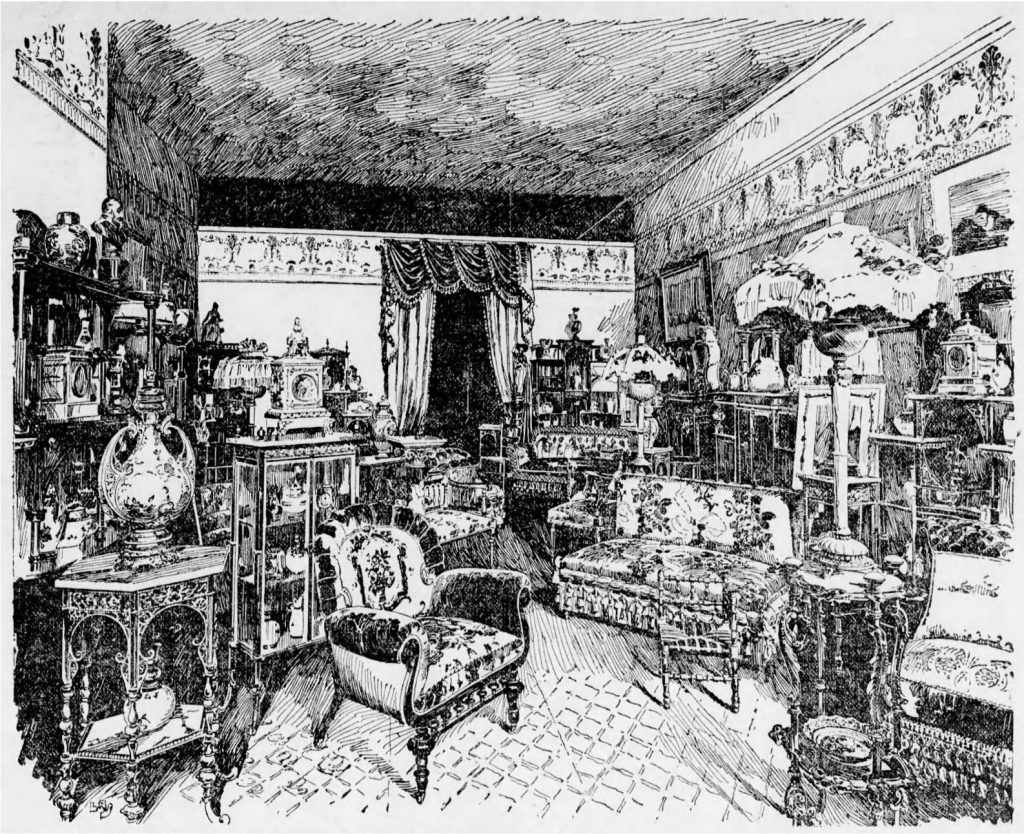

If you could peek into the home of a wealthy Victorian-era American family, it would probably look cluttered to our modern eyes. Bare rooms were equated with poor taste, low morals, and poverty, while displaying expensive objects was a sign of style, culture, and status. Vases, figurines, decorative boxes, fans, teacups, miniature paintings, curios, and much more filled nearly any flat surface, from mantles to tables to sideboards.

The Second Industrial Revolution (roughly 1870–1914) was creating an abundance of “nouveau riche” in America, people recently made wealthy by railroads, steel, and other new industries. Eager to imitate the aristocracy of Great Britain and Europe—and to showcase their new wealth and worldliness—they filled their homes with costly objets d’art. These decorative objects eventually came to be known as “bric-a-brac.”

- Go here to read an 1887 newspaper article about bric-a-brac selling for insanely high prices

Though items sold as bric-a-brac supposedly had historical ties, antique origin, or exotic provenance, realistically it was a term for expensive items with no practical use—which is probably why an 1875 New York Times article defined bric-a-brac as “elegant rubbish.” Still, bric-a-brac was in such high demand that an industry sprung up to procure and sell it. Newspapers carried stories of people spending incredible sums of money to expand their collections, and ads for bric-a-brac sellers abounded in the papers.

Bric-a-Brac’s Decline

This “bric-a-brac mania,” as it was sometimes called, had its acme in the 1870s and 1880s. But as is the case with many expensive things, a knock-off market of cheaper, inauthentic bric-a-brac came into being. This affordable, mass-produced bric-a-brac allowed people of the middle and even working classes to embrace the trend and buy bric-a-brac for their own homes.

- Go here to read about the knock-off market for bric-a-brac in an 1885 newspaper

The wide availability of inexpensive bric-a-brac meant it no longer implied social status and wealth, however, and its popularity among the upper class began to wane. Around the same time, attitudes about ostentatious displays of wealth began changing, and interior design preferences shifted toward simpler and more utilitarian styles. On top of that, late 19th-century America was hit by a series of economic panics—perhaps putting more nails in bric-a-brac’s coffin. Gradually, the term “bric-a-brac” began to take on the connotation that it has today—nearly synonymous with “knick-knack” rather than “objet d’art.”

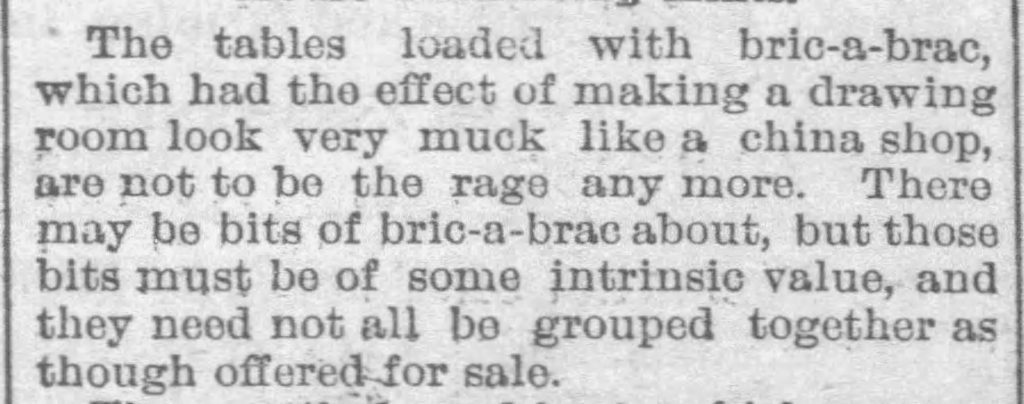

The rejection of the bric-a-brac trend can be clearly seen in newspapers from the late 1880s through the early 20th century.

One Pennsylvania newspaper wrote in 1895:

And this 1906 article even provided questions to help the reader cut down on bric-a-brac:

20th-Century Clutter

The end of the 19th-century bric-a-brac craze wasn’t the end of indoor clutter, obviously. In fact, there seems to have been somewhat of a resurgence of bric-a-brac in the 1920s, though the onset of the Great Depression likely had a dampening effect.

- Go here to read a 1926 article about bric-a-brac’s 1920s comeback

But America’s post-war economic boom in the late 1940s through the early 1970s gave people more discretionary income than ever before. Perhaps as a result of this new post-war buying power, home decor trends in the late 1950s swung back toward a “controlled clutter” look. And articles promoting “clutter rooms” (rooms devoted to odds and ends) ran in the papers in the 1960s. So is it any surprise that decluttering articles became increasingly ubiquitous in newspapers in the decades after the economic boom?

The Pendulum

America’s views on the use of clutter in home decoration seem to be a pendulum, swinging back and forth between embracing a cluttered look and its rejection. Right now, our society appears to be firmly rejecting it, as typified by the incredible popularity of Marie Kondo and her method. (Related examples of this desire for simplification are found in the “tiny home” movement and the backlash against the “fast fashion” industry.)

But as history has shown us, who knows when the pendulum will swing back the other way? So you might not need to throw out grandma’s antique tea set just yet.

Learn more about bric-a-brac by searching Newspapers.com. Or if you’re interested in reading some vintage decluttering articles, start with these:

- “Crusade Against Clutter” (The Atchison Daily Globe, 1905)

- “Rid the House of ‘Clutter’ to Cheer It,” (The Port Huron Times-Herald, 1913)

- “Bric-A-Brac Homes,” (The Boston Globe, 1926)

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for more interesting historical content like this!

At one point, Victorian bric-a-brac was thought to make a room look larger. The idea was that the more things the eye had to take in, the longer it would take and the room would seem more spacious. Honestly, the only way a person could have all of that *junk* was if they had a team of housemaids – or pixies – to dust it all.

I thought my mom was a hoarder! She had hundreds of figurines setting on every flat surface of the house. So much so it took 4 days to empty the home after both my parents passed away. We thought of it all as semi-junk, we didn’t realise it was her treasure.